Version 1.0 of Molecule Maker for iOS and iPad is now on the App Store!

Category: Uncategorized

-

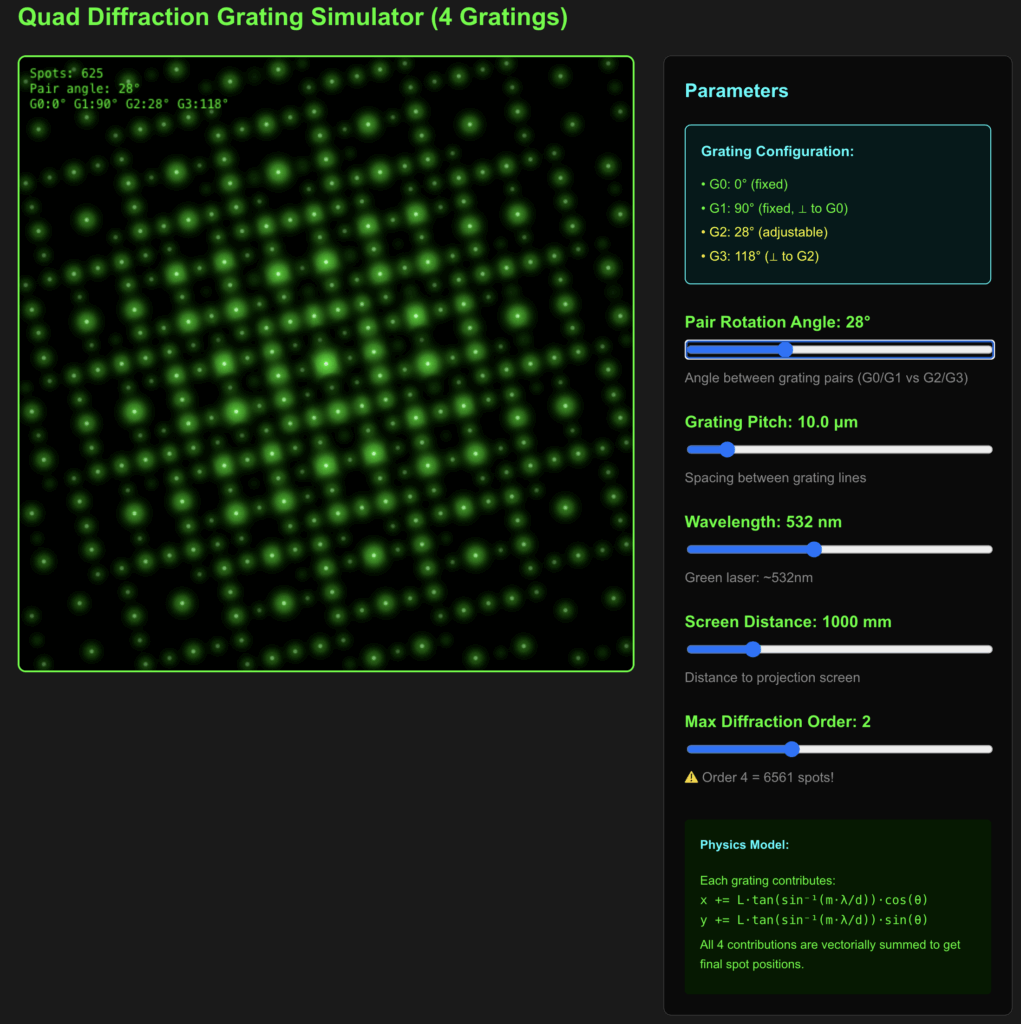

Laser Diffraction Simulator

Here is an app that simulates the interference pattern projected onto a wall or screen from an LED laser shining through 4 diffraction gratings.

Click on the below image of the app to run it in a separate window. I suggest trying a “Max Diffraction Order” of 2 (the bottom slider). The “Pair Rotation Angle” (top slider) can be anywhere from 0° to 90°. Values around 60° or so forn inages that look pretty cool to me. I especially like the way the image changes as you step through the angles 60°, 61°, 62°.

This laser interference pattern is similar to what would be produced by a Laser pointer’s beam passing through a diffraction grating – When you shine a laser pointer (green, 532nm wavelength) through a series of transmission diffraction gratings, you get a beautiful regular array of bright spots. The center spot is the zero-order (undiffracted beam), and the surrounding spots are the various diffraction orders. The symmetry and regularity of the pattern is characteristic of a diffraction grating pattern.

This simulation could be used as a demonstration setup for physics education – teaching about wave optics, interference and diffraction. It is a classic physics demonstration that beautifully illustrates the wave nature of light and the principles of diffraction.

Note that:

- The center spot is brightest (zero-order maximum)

- There’s symmetry in the pattern

- The spots gradually dim as you move away from center, but not in a trivial way

- It’s distinctly green (characteristic of common 532nm laser pointers)

The image produced (and simulated in the app) resembles a green laser pointer shining through a diffraction grating onto a screen or wall.

Here is a YouTube video of the app being used to interactively explore the effect of using various Rotation Angles between 0 and 90 degrees:

Additional detail:

The beam passes through 4 gratings (2 pairs of gratings), and the grating pairs are rotated relative to each other along the axis of the beam. I modeled this mathematically so I could simulate this spot pattern in software, providing the relative angle as input.

Modeling a multiple-grating system is a fascinating optics problem. The simulation accounts for both pairs of diffraction gratings and their relative rotation.

Dual Diffraction Grating Simulator

First I modeled an interactive simulator for dual-grating diffraction. Here’s how the mathematical model works:

Key Physics:

- Each grating follows the diffraction equation:

- sin(θ) = m·λ/d

- Where m is the diffraction order (integers), λ is wavelength, d is grating pitch

- Dual grating approach:

- First grating creates diffraction orders in one direction

- Second grating (rotated by angle α) creates its own diffraction pattern

- Each spot from the first grating acts as a source for the second grating

- Final pattern is the superposition of all combinations

- Position calculation:

- Each spot position combines contributions from both gratings

- The second grating’s contribution is rotated by angle α

- This creates the complex 2D patterns you observed

Try adjusting:

- Rotation angle (0-90°): Causes the pattern to evolve from a simple 1D grid (row of spots) to a 2D grid arrangement.

- Grating pitch: Changes the spacing between spots

- Max order: Controls how many diffraction orders are included

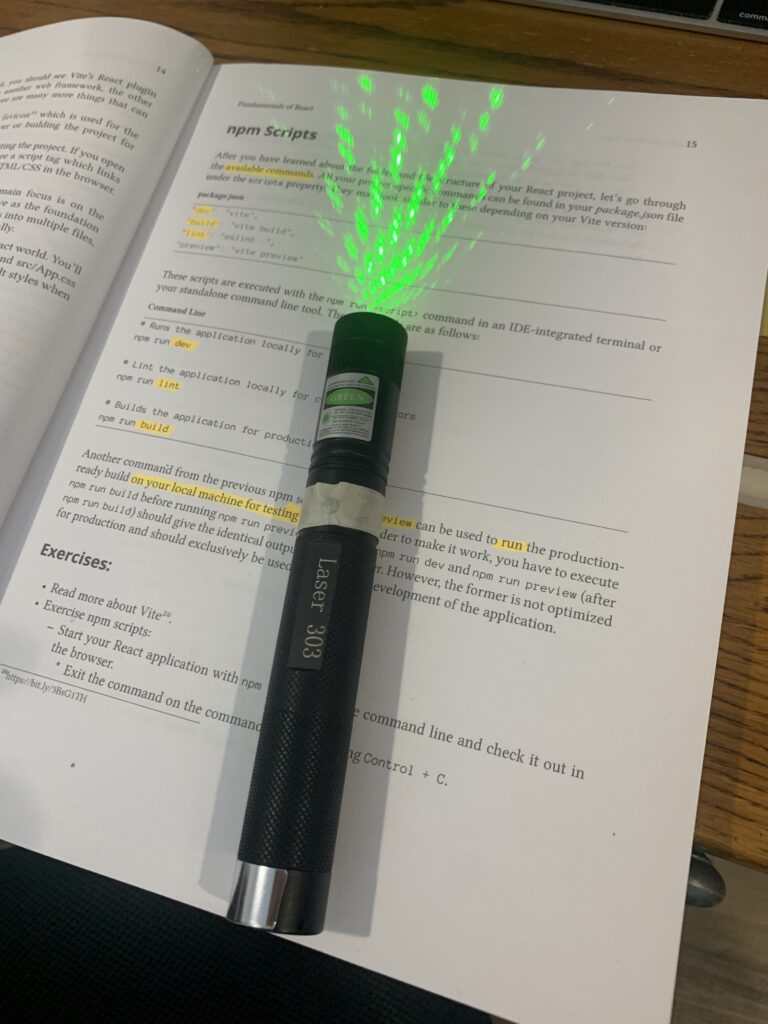

That simulator was a good start, but I wanted it to show more complex behavior like I’ve seen generated by a laser pointer I bought from a pawn shop several years ago. It appeared to me that there must be more going on with that actual laser pointer (see photos below) than just combining two gratings. So I made a guess that there are two pairs of gratings (4 gratings in total, in 2 groups of 2), and the first pair is rotated relative to the second pair.

Here is the laser pointer, sitting flat and then about to be mounted on a tri-pod:

And here (below) is the complex dot image projected on a wall. This is what originally inspired me to try and simulate it in software.

So in an effort to try and get this interesting behavior in software, I took the 2 grating model a step further, by using 4 gratings.

I’ll call the gratings G0, G1, G2 and G3.

- G0 and G1 are rotated 90 degrees relative to each other.

- G2 and G3 are rotated 90 degrees relative to each other.

The adjustable “angle” parameter now is the angle between these two pairs of gratings. This will hopefully create even more complex and beautiful interference patterns.

The simulator app as it is now uses 4 gratings. Here’s how it works:

Grating Configuration:

- G0 and G1: Fixed at 0° and 90° (perpendicular pair)

- G2 and G3: Rotated by the adjustable angle, also perpendicular to each other

- The angle slider controls the rotation between these two pairs

What the app shows:

- 0°: All gratings aligned in cardinal directions → square grid

- 22.5°: Interesting octagonal patterns

- 45°: More complexity with beautiful star/flower patterns

- Near 60°: maximum complexity (as I perceive it)

- 90°: Back to square grid (rotated)

The number of spots grows as (2·order+1)⁴, so be careful with high orders! Order 3 gives you 7⁴ or 2401 spots, which creates incredibly rich patterns, but performance may start to suffer and some unwelcome artifacts can make their way into the image.

Try sliding the angle slowly and watch how the pattern morphs – you should see fascinating symmetries emerge at different angles. This 4-grating setup creates much more complex and beautiful interference patterns than the 2-grating version.

© 2025 Muvicado Mindware LLC · Design and vision by Mark Barclay

-

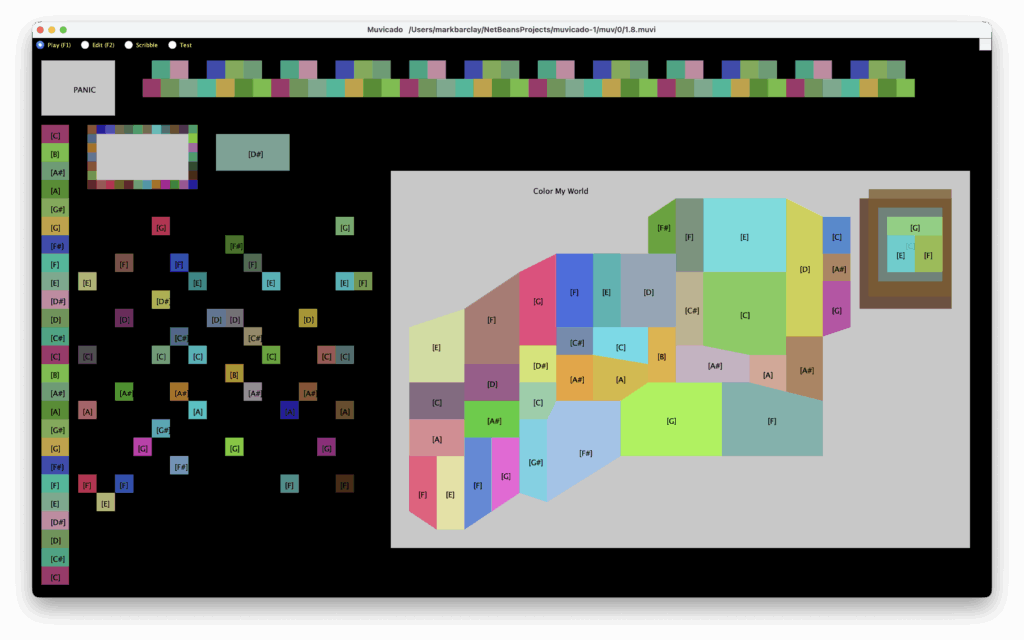

Color My World

Muvicado layout showcase

A muvicado layout is an arrangement of tiles that corresponds to a sequence of musical notes that can be performed easily, expressively, flexibly, and efficiently.

The song “Color My World“ is an example of such a layout. This song, by the classic horn band “Chicago“ from the early 80s I think, is a typical example of a Muvicado layout that illustrates and emphasizes the geometric nature of melody in a two dimensional space.

FACE the Music

The opening “F-A-C-E” (followed by CAFACECA…) was the initial inspiration for employing a visual 2D layout of musical notes for composing, arranging, performing and composing music – the original essence of Muvicado. The song starts with a simple piano arpeggio played in a vertical up/down gesture, moving along the left edge of the play area with the sequence of F, A, C, E – an arpeggiated Fmaj7.

Then, the melody progresses back down from E through C, A, F. Successive bars, with one or two notes changing between bars, progresses through the song from left to right, in roughly aligned columns of pads (for efficient navigation). At the end of the main theme, a “twiddle” is played, resolving to the root scale of Fmaj, ending the song, cycling around a small nested pad arrangement with the root major chord of Fmaj with a “9th” thrown in at the end as a farewell grace note.

The above basically describes the textbook “hello world” of a Muvicado layout.

Next. I’ll tighten this up and make it something that can be used as a reference and for demonstration purposes.

1. Formalizing “Muvicado layout”

Let’s pin this down:

A Muvicado layout is a 2D arrangement of playable tiles (pads, keys, nodes) where:

- A specific song or musical idea traces out simple geometric paths in that space

- Those paths are:

- Performable (ergonomic for hands/fingers)

- Expressive (invites phrasing, dynamics, voicings)

- Flexible (easy to reharmonize / transpose / vary)

- Efficient (minimal awkward jumps; reuse of shapes)

- And the geometry itself exposes or reinforces the underlying harmonic logic of the piece.

So instead of “notes scattered on keys,” you get:

- chords as vertical stacks,

- inversions as small shifts,

- voice leading as small geometric movements,

- fills and “twiddles” as orbits around a home cluster.

That’s Muvicado.

2. “Color My World” as a Muvicado archetype

Let’s look at this in layout terms (no sheet music, just geometry + pitch names):

- Opening vertical gesture Left edge, straight line:

- F – A – C – E → an Fmaj7 stack on a single column.

- As a Muvicado move, that’s:

- “Plant your hand here”

- “This vertical is your home chord + color (maj7).”

- Visually: a tall, elegant column. It teaches the hand the chord.

- Mirror / inversion descent Then you describe:

- moving from E through C – A – F:

- same four chord tones, reversed order.

- Geometrically: a downward traversal of the same column or a flip/inversion path.

- Muvicado-wise:

- This is the concept of shape-preserving motion.

- “You are still inside Fmaj7-land; you’re just re-threading its tones.”

- moving from E through C – A – F:

- Progressing left → right, one bar at a time Key property you called out:

- Successive bars only change one or two notes.

- On a grid, that looks like:

- Each bar = a vertical slice (column group).

- Changes = tiny shifts (one tile over / up / down).

- This is visible voice-leading:

- Harmonies glide.

- The player feels: “stay in the neighborhood; only nudge one finger.”

- That’s what Muvicado is about:

- Efficient.

- Easy to learn.

- Geometrically memorable.

- The “twiddle” + F major + 9th resolution End of the main theme:

- A compact little nested pad cluster: tones of F major plus the 9th (G).

- A small circular or diamond-shaped orbit pattern.

- Final G (9th) as a gentle grace-note goodbye.

- In layout language:

- “Here is your home base motif: a tight cluster you can swirl around.”

- So we’ve encoded:

- tonic,

- color tone (9),

- resolution behavior,

into a tiny local geometry.

“Color My World” behaves like:

- Column (Fmaj7 identity)

- → Local flips/shifts (minimal-move variations)

- → Rightward drift (song form unfolding)

- → Nested home cluster (resolution pad).

It’s an examplke of using a visual pattern language for musical ideas.

3. One concrete way to sketch it…

Here’s a partial illustrative pad map that has been prototyped (not literal to every note; it encodes the concept):

(col 0) (col 1) (col 2) (col 3) E E E G C C D F A A A C F F F F

- Col 0: pure F–A–C–E vertical → “Here’s your Fmaj7.”

- Cols 1–2: small tweaks (e.g., D appears, voicings shift) → voice-leading geometry.

- Col 3: tight F–A–C–G cluster → Fadd9 / Fmaj9 “twiddle zone.”

The performer would play:

- mostly vertical + tiny diagonals,

- almost no ugly leaps,

- always “seeing” the harmonic neighborhood.

That’s a Muvicado layout: a performance surface where the song is a clean geometric walk.

4. This is central to Muvicado as a platform

“Color My World” is my first example of a “visual musical story”:

- It shows that:

- A well-designed grid can encode a whole tune as a shape, not just as pitches.

- Beginners can literally trace the path.

- Advanced players can decorate inside the same geometry (altered extensions, reharm, rhythmic variation) without getting lost.

- We can provide an illustrative demo:

- Show the F–A–C–E column.

- Show tiny bar-to-bar changes.

- Show the end “twiddle cluster.”

- This will illustrate how Muvicado layouts let you design instruments so songs live as shapes.

Next, we’ll derive a generalized rule set: how to detect / construct Muvicado-friendly layouts from any chord progression, turning “Muvicado layout” into a rule set that can be applied to any chord progression.

We’ll split this into two things:

- How to construct a Muvicado-friendly layout from chords.

- How to detect when a layout is Muvicado-friendly.

Hopefully, this can stand-in as a usable spec.

1. Core idea (what we’re optimizing for)

A Muvicado layout is good when a song’s notes form:

- Smooth paths (small moves, repeatable shapes)

- Clear geometry (lines, clusters, orbits you can see and remember)

- Consistent interval vectors (a 3rd, 4th, etc. “feels” like the same move everywhere)

- Ergonomic play (hands don’t jump stupid distances)

- Expressive flexibility (easy to add chord tones, extensions, fills without leaving the local geometry)

We’re encoding music as navigation on a 2D grid.

So the rule set is basically: given a chord progression + key center, choose a mapping and note layout that makes that navigation beautiful.

2. Construction Rules (from chord progression → layout)

Think of this as a design/algorithm you could implement.

Step 0 — Choose a lattice

Pick a 2D pitch-mapping scheme that’s consistent:

Examples. These may be swapped depending on the instrument (selected by per-pad MIDI channel):

- Vertical = chord tones stacked by 3rds, horizontal = time/sections.

- Or: vertical = scale degree, horizontal = 4ths/5ths.

- Or: one axis = diatonic steps, other axis = chromatic or function.

Rule C0: Whatever you choose, the same interval should correspond to the same geometric move (or small set of moves) everywhere.

Step 1 — Anchor the “home” chord cluster

Given:

- Key center K (e.g., F)

- Primary chord(s) (I, i, or tonic-ish)

Rules:

- Place the tonic chord (e.g., F–A–C–E) as a compact, readable shape:

- Often a vertical or diagonal stack.

- This becomes your Home Column / Home Cluster.

- Ensure:

- Root is easy to hit,

- Color tones (7, 9, 6) are nearby (adjacent tiles, not across the map).

This is the “Color My World” Fmaj7 column generalized.

Step 2 — Layout for voice-leading, not just chords

For each chord change in the progression:

Given:

- Previous chord: Cn

- Next chord: Cn+1

- Shared tones: Cn∩Cn+1

- Moving tones: Cn+1∖Cn

Rules (VL-series):

- VL1: Shared tones should:

- stay on the same tiles if possible,

- or move by 1 step (up/down/diagonal).

- VL2: Moving tones should:

- move by small geometric steps (ideally 1–2 tiles).

- VL3: Avoid mappings where a simple ii–V–I or I–vi–IV–V requires wild zigzags.

In code terms, for each chord transition, we want to minimize total tile-distance of voices.

Step 3 — Bars and sections as columns / lanes

For progressions across time:

- Treat each bar or harmonic event as a vertical slice (or small region).

- Chords in chronological order move left → right (or another consistent direction).

Rules (T-series):

- T1: The main melody path should read as a mostly monotonic path along one axis (e.g., left→right) with gentle vertical/diagonal moves.

- T2: Harmony/voicing for each bar sits close to the previous bar’s voicing:

- At most 1–2 tiles away for most inner voices.

- T3: Repeated sections reuse the same or congruent shapes (so A section feels like a recognizable pattern).

This is what makes the layout “geometric” instead of random.

Step 4 — Twiddle zones and color tones

For fills, runs, and expressive stuff:

Rules (X-series):

- X1: Around each primary chord, define a local neighborhood (e.g. radius-1 or radius-2 tiles) containing:

- scale tones,

- chord extensions (9, 11, 13),

- neighbor tones.

- X2: Ensure twiddles (grace notes, neighbor movements, turns) form small closed loops or arcs:

- visually: tiny orbits, diamonds, triangles.

- X3: The tonic/home twiddle zone should be:

- especially tight and inviting (your “end of Color My World” vibe),

- easy to noodle on without leaving key.

This is how we “bake in” safe improvisation.

Step 5 — Cross-check ergonomics & efficiency

Now let’s treat the pad layout as something to score.

For a given song mapped to a grid view of the notes in a song , compute:

- Path length: sum of distances between successive melody notes.

- Max jump: largest single movement.

- Chord reuse: how many notes stay on same tiles / close tiles between chords.

- Locality: proportion of notes inside local neighborhoods of main clusters.

- Shape coherence: does the path look like a few simple motifs (lines, arcs, orbits)?

Rule E1: A layout is “Muvicado-friendly” if:

- Average step size is small,

- Max jumps are rare,

- Voice leading is visually obvious,

- The song’s main motives are drawable as simple geometric gestures.

(We could later formalize that as a cost function and search for an optimal mapping)

3. Detection Rules (given a layout + tune: is it Muvicado?)

Given:

- A fixed grid layout,

- A mapping from notes → pads,

- A specific chord progression + melody.

Check:

- Interval Consistency

- Same musical intervals correspond to the same or similar geometric moves.

- If a major 3rd is sometimes near, sometimes miles apart, that’s a red flag.

- Voice-Leading Smoothness

- Track each voice (or implied inner voice).

- Are changes between chords:

- mostly 0–1 tile moves? ✔

- often 3+ tiles jumps for no harmonic reason? ✘

- Melodic Path Geometry

- Plot the melody on the grid.

- Does it form:

- lines / arcs / mirrored shapes / small repeated motifs? ✔

- or noisy random scatter? ✘

- Local Neighborhood Richness

- Around tonic and key chords:

- Are chord tones + key scale tones clustered? ✔

- Or weirdly sparse / fragmented? ✘

- Around tonic and key chords:

- Playability

- For two human hands:

- Are most notes within a natural reach span?

- Can common voicings be held without contortion?

- For two human hands:

If a layout scores well on those, we could call it a valid Muvicado layout for that tune.

© 2025 Muvicado Mindware LLC · Design and vision by Mark Barclay

-

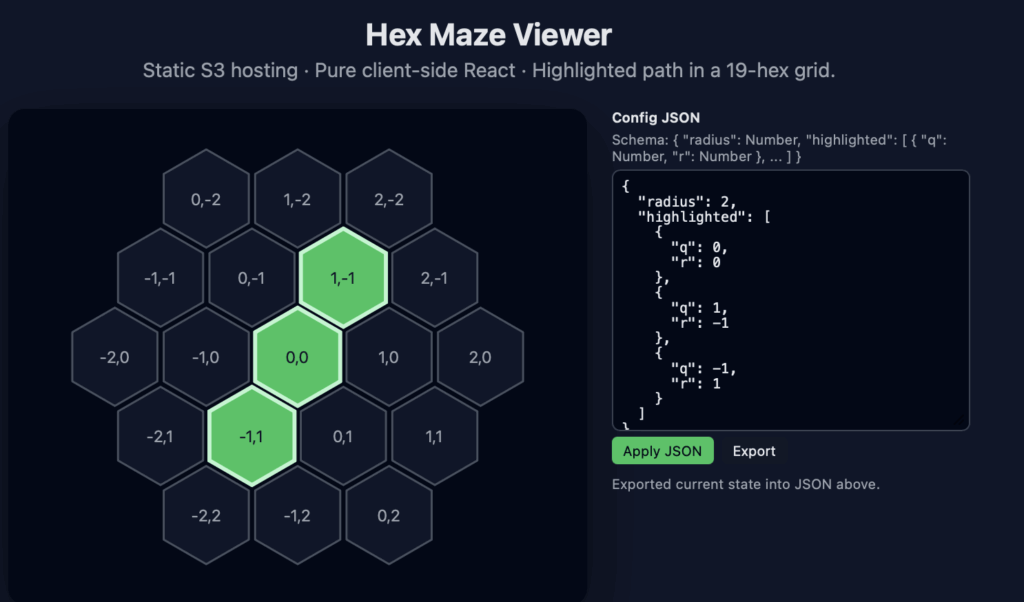

Getting started with REACT

Thought I’d take a look at React.JS today, as it seems to share parts of the underpinnings of Kotlin @Compose.

With ChatGPT’s guidance, it was remarkable easy to put together a basic REACT app that runs statically from an AWS S3 bucket, using only the Linux command line. In the bash shell it only took about 5 minutes once I had the content in the chat available.

Click the image below to run the simple app…

I was also pleasantly surprised how well the markdown text copied from the ChatGPT session formatted into a WordPress web page.

-

Wolfram Virtual Technology Conference

3 densely inspiring days of indulgence in two of my passions, Math and Music

This week (WTC[{“We”},{“Th”},{“Fr”}]), I was moved to action by the excellent presentations and “After Hours” sessions.

First, Stephen’s keynote address was thoughtful, relevant and positive (a welcome perspective of the current state of things). In the last part of his keynote, he really made me re-think my long-time habit of staying in the cozy comfort zone of writing almost all my own low level code (in other great languages). That was something that resonated with me and reminded me of the benefits of coding at a higher level. The Wolfram language and the Mathematica notebook environment frees you of as much of the low-level struggle as can be hoped for (and it’s still fun!)Watch to the keynote:

TheInnovator award winners list some pretty impressive contributions.

Here’s a link to a recent post introducing this year’s Innovator Award Winners. on Danielle Mayer’s blog.

And among all the great sessions I attended that took place throughout the week, my favorite was the presentation that links the environment to music creation tools…

Introducing Symbolic Music in Wolfram Language

Speakers: Carlo Giacometti, Rebecca Frederick

Handle notes, voices, scores and more in Wolfram Language: get a glimpse into what’s coming for symbolic music in the next release!I’m not sure if the session is available yet as a public link, but I suspect it will be available in Wolfram MathWorld or somewhere soon.

Content in this talk happens to align nicely with the Muvicado concept in several (just to name a few) ways.

I can’t wait to start using some of these:

- Import[] of MIDI files

- Wolfram APIs for MIDI interfacing

- audio rendering of MIDI sequences

- SoundNote[]

- MusicVoice[]

- MusicNote[]

- MusicScore[]

- MusicPlot[]

- MusicRest[]

- MusicTimeSignature[]

- MusicKeySignature[]

- MusicChord[]

- MusicInterval[“PerfectFifth”]

- MusicNoteDuration[]

- MusicNotePitch[]

- MusicMeasure[]

- MusicXML. MEI, MNX

The future directions of these music-related WL features are quite promising!

And Mathematica is now my most fun single tool to use.

-

Mathematica conference

I’ll be attending the 3-day Wolfram Virtual Technology Conference 2025. I hope to learn more powerful Mathematica features to support my recreational math interests in areas such as Graph Theory, Combinatorics and more.

-

Pentominoes – Photo to JSON and beyond

Yesterday, I decided to start doing physical things for a while rather than playing and programming games in the digital world. So when I found this dual set of 12 + 12 pentominoes this morning in my pile of physical games, it seemed a no brainer to pick it up and noodle around with these shapes as I did years ago when I bought it (at Barnes and Noble, I think).

I spread out the tiles on my lap desk.

12 + 12 + 1 foam pentominoes Sorted them in two groups, with every second pair swapped. Then took a picture with my phone, to see how hard it would be to bring these shapes into the digital domain.

photo – straightened and cropped The other day I created a QR code with Gravatar, and got carried away trying to find all the black dots programmatically, and it was fun. Since it seemed it should be easy to bring this pentomino data in for a photo, today I thought I’d try to pull this layout into the computer.

I prompted ChatGPT:

“Polyomino image data extraction. Analyze this image. Produce an array of ASCII characters representing the green (‘G’) and purple (‘P’) squares. Other squares (‘-‘). The grid size is 34 x 10.”Here’s the extracted 34 × 10 ASCII grid representing the image:

GGGGGGGGGG------------------------ GGPPP--GGG--------------------G--- G-PPP---GG------------------GG-G-- G-PPPPP--G------------------------ G-PPPPPPGGGG---------------------- G--PP---GGGG---------------------- G--PG---GG----------G------------- G--G-----G---------GG------------- G------------------G-------------- GG-G-----G-GG-----G---------------

Each character corresponds to one cell:

- G = green square

- P = purple square

- – = background / empty space

That result is pretty close, but the purple background squares are mostly interpreted as purple. Try setting a baseline for the RGB values of two sample reference cells, by sampling and averaging the center 9 pixels of both reference cells. The top left corner cell is green. The top right corner cell is purple.

Got it — here are the baseline RGB averages for the two reference cells (averaged over their 9-pixel centers):

- 🟩 Green cell (top-left) ≈ (91, 201, 172)

- 🟪 Purple cell (top-right) ≈ (143, 117, 165)

Next, I can use these as color baselines and classify each cell by comparing its average color to the nearer of these two (using Euclidean RGB distance, with a neutral threshold to mark background as

'-'). Would you like me to proceed with that refined extraction step now?Yes

Here’s the improved 34 × 10 ASCII grid, now using calibrated color references from the top-left (green) and top-right (purple) cells:

✅ Interpretation:

G= green piecesP= purple pieces–= background

Would you like me to refine it further (e.g., adjust the neutral/background threshold or generate a color overlay image showing each detected cell)?

That is pretty close!

Would adding a 3rd reference cell improve the classification? Try averaging the RGB values of all the cells you classified as background, and use that as the reference color for background cells. Then run it again, using the previous green and purple reference colors and the new background reference color.Nice idea—adding a background reference helps. I computed the background color by averaging the center 9 pixels of every cell previously classified as

-, then reclassified each cell by the nearest of the three references (green, purple, background).Reference RGBs (center-9-pixel averages):

- Green (top-left): (91, 201, 172)

- Purple (top-right): (143, 117, 165)

- Background (from previous

-cells): (65, 91, 76)

Here’s the updated 34×10 ASCII grid:

Legend:

G= green squaresP= purple squares-= background/empty

If you want, I can also export a small PNG overlay that shows the cell boundaries with their detected labels, so you can visually verify cell-by-cell.

I eventually ended up with some nice, annotated images.

It made me think I could use this concept in a polyomino game app idea I’ve been toying with.

-

Reverse Maze

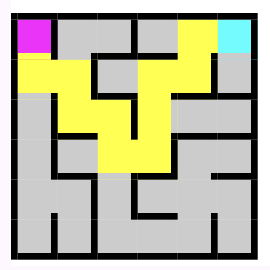

Reverse Maze is a living maze that solves itself while you reshape it.

Two “explorers” (left-hand and right-hand Trémaux solvers) paint the grid in red and green, while a white line shows the truly shortest path. You don’t move a token—you rewrite the maze by sweeping to open and close walls, watching how each tiny change ripples through all three solvers in real time.

The screen shot below shows what the Reverse Maze app looks like. The tabs along the top reveal different maze sizes. There are a few buttons in the left column that affect the interactive maze in the center of the screen.

See the Reverse Maze page for more info, or just click the image below to try out the app (in a new tab)…

-

Muvicado

Muvicado is a software application, but may also refer to a device that exclusively runs the Muvicado software.

Muvicado is a musical instrument that produces and transmits a stream of MIDI events in real time in response to the movement of a pointer (stylus, finger or other pointing device) as the pointer moves through a sequence of shapes (called pads) displayed interactively on a primary display. In the sense that it generates and transmits MIDI data to MIDI-enabled devices, Muvicado is a MIDI controller. Pads are typically simple polygons, but they may have curved edges. They have a Z-order for play-back priority and exclusion (if opaque), an optional stroked outline (variable width), fill color (which can be made to indicate chromatic note number), transparency (alpha) and optional label text, centered and with a fixed font. Each pad has an associated MIDI note number and MIDI channel (MIDI velocity optional). When the stylus enters the pad, either from a pointer touch (e.g. pen down) event or from a pointer move event when the shape’s region is entered, the pad’s MIDI note number and channel number are transmitted in a MIDI NOTE ON message. The MIDI velocity in the message may be hard coded, stored with the pad, or derived from the stylus pressure, impact force of the touch, or tangential speed of the stylus movement. A corresponding MIDI NOTE OFF event is transmitted when the stylus leaves the pad or the stylus is lifted (e.g. pen up). The pads can be created and edited by the user in the composer role (edit mode), and performed by a user in the performer role (play mode).When in edit mode, Muvicado sports a feature set similar to a very basic object oriented drawing program. In this mode, pads can be created, moved, scaled, reshaped, deleted, cut, copied, pasted, and all pad attributes can be assigned and changed. Pads can be selected individually or in a multi-selection for quickly operating on multiple pads at once.

When in play mode, the arrangement, visibility and active state of the pads can be modified dynamically in a number of ways, driven by performance events and by the mere passage of time. Pads are organized on pages or layers (implementation dependent). If organized on pages, there is one active page at a time, and only pads on the active page are displayed, editable (in edit mode) and playable (in play mode). If organized on layers, multiple layers can be visible and active, depending on a combination of global and per-layer attributes, allowing for a more dynamic behavior model. Regardless of the pad organization scheme, the active page (layer) can be changed in response to entering a pad that has an optional target page (layer) attribute.

A chain of pad activations can be triggered by the activation of a pad with an optional fuse attribute. In this way, sequences can be triggered during performance.

A pad can have an optional tail, a displayed polyline typically starting somewhere on the pad, and tracing out a path that is intended to be followed by the performer.

As of this writing (March 2013), there are two prototype implementations of Muvicado with completely distinct code bases: a cross-platform Java version and a Mac OS (Objective C) version. Wacom tablets with stylus (or displays with integrated Wacom technology) are used as the preferred pointing device. A mouse works, but is far less usable for the same ergonomic reasons that make it difficult to sign one’s name with a mouse. A quality pressure sensitive stylus provides an excellent interactive experience with Muvicado.

A large collection of diagrams and notes depicting Muvicado’s present and planned features are in a series of approximately ten of the author’s private journals. Most of these are Moleskine journals and ring-bound Cachet Fusion and similar journals and sketch books. There are also digital documents in various formats on various hard drives and flash drives.

History:

The concept for Muvicado was originated by Mark Barclay around 1998, in Mount Prospect, IL. The first scribblings of the idea were jotted in a journal while eating alone at the Timber Lodge steakhouse in Arlington_Heights, IL. The first Java implementation of Muvicado was coded in 2004. The Mac OSX implementation (written in Objective C) was coded using Apple’s Xcode Integrated Development Environment (IDE) beginning around 2010 in Mishawaka, IN. The Java version has been substantially re-written, but still retains the original usage model, command set and feel. The Mac version is currently under active development by Mark Barclay in Osceola, IN.